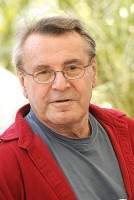

Milos Forman

Milos Forman (1932-) won acclaim in the sixties, at the time of what is now called the Czech New Wave. He made a breakthrough with two films, which entered international distribution as Black Peter (1964) and Loves of a Blonde (1965), the latter nominated for an Oscar. Both were shot with minimum budget, featured non- actors and were partly improvised. Thanks to attentive crew they hardly feel amateurish, at least not in the negative sense of the word, but they certainly do feel authentic. Major critical success, and second Oscar nomination, came with The Firemen’s Ball (1967), a very sour comedy, which dealt both with themes general and particular for the Czechoslovakian regime. As in case of other films of the time, the impossibility of dealing with politics head-on forced filmmakers to find more subtle ways of commenting the current affairs. It’s one of the reasons why many of the films are still appealing today.

Milos Forman (1932-) won acclaim in the sixties, at the time of what is now called the Czech New Wave. He made a breakthrough with two films, which entered international distribution as Black Peter (1964) and Loves of a Blonde (1965), the latter nominated for an Oscar. Both were shot with minimum budget, featured non- actors and were partly improvised. Thanks to attentive crew they hardly feel amateurish, at least not in the negative sense of the word, but they certainly do feel authentic. Major critical success, and second Oscar nomination, came with The Firemen’s Ball (1967), a very sour comedy, which dealt both with themes general and particular for the Czechoslovakian regime. As in case of other films of the time, the impossibility of dealing with politics head-on forced filmmakers to find more subtle ways of commenting the current affairs. It’s one of the reasons why many of the films are still appealing today.

In 1968 he traveled the world with Jean- Claude Carriére, an established screenwriter, who worked on several Forman’s films. The director was confronted with the Soviet invasion while in France. He managed to get his family out of the country, but after some time his wife and two sons returned to Czechoslovakia. He decided to stay abroad. Needed to add that most New Wave directors that voiced critics of the regime and did not manage to emigrate, were prevented from staying in the film industry. With a sad exception of several, who decided to make compromises with the Party and agreed to make propagandist and/or politics- free crime movies and comedies. Most of these normalization- era productions, apart from being clumsily shot and badly acted, usually lack any substance and have little right to be paid attention to. There were exceptions like Věra Chytilová, who managed to persuade the right people to let her shoot, or František Vláčil, who was not very politics- oriented and was lucky enough to make films so complex that the administration probably didn’t even understand them.

The following story is well known. Forman left for the US and soon gained recognition. In 1975 he made his arguably best film, One Flew Over The Cokoo’s Nest. Most of his subsequent work very successful and awarded, although some critics point out that his work tends to be closer to the mainstream with every film. Amadeus is widely considered Forman’s lovely crowd- pleaser, although the film was starless, not very expensive and its huge success was a bit of a surprise. And is it a problem if a great director makes a somewhat compromised, but fine, intelligent film for everyone? Is it what an artist should do or is it selling oneself short and going for the bucks? Difficult to say. In the end it depends on what one asks of an artist.

In his films Forman concentrates on the individual facing some form of an oppressive or backward system. He does not necessarily condemn the system altogether- in Hair it’s US military and he is an admirer of the US and a US citizen since 1975. What he shows is a single wrong- the Vietnam war and a clash of independent spirit with the machinery that thinks of people as a mass. His sympathies lie with the individual even in some of the more difficult cases, like that of the porn magnate Larry Flynt in his 1996 movie.

Forman is now a Czech- born American director, separated from his homeland for too long to return and work here. But he does keep the connection. His sons, Matěj and Petr, are successful playwrights and stage actors and he joined them a year ago as the director of a new version of a sixties play by Jiří Suchý, The Well- Paid Walk (Dobře placená procházka). Since 1989 he also appeared in a number of Czech documentaries, for instance as a narrator of the 1991 doc “Why Havel?” by another Czech New Wave émigré Vojtěch Jasný.